This recipe in the King Arthur Baking School cookbook is titled French Bread, but it’s similar to “straight” breads made in multiple bread traditions. I love this kind of bread.

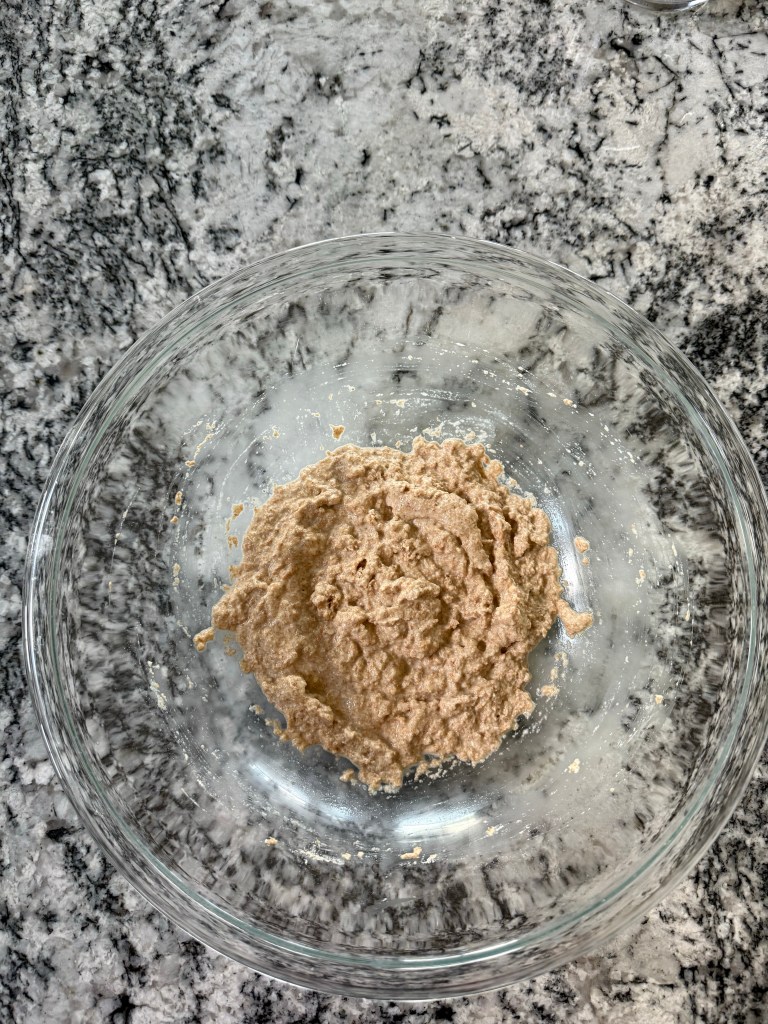

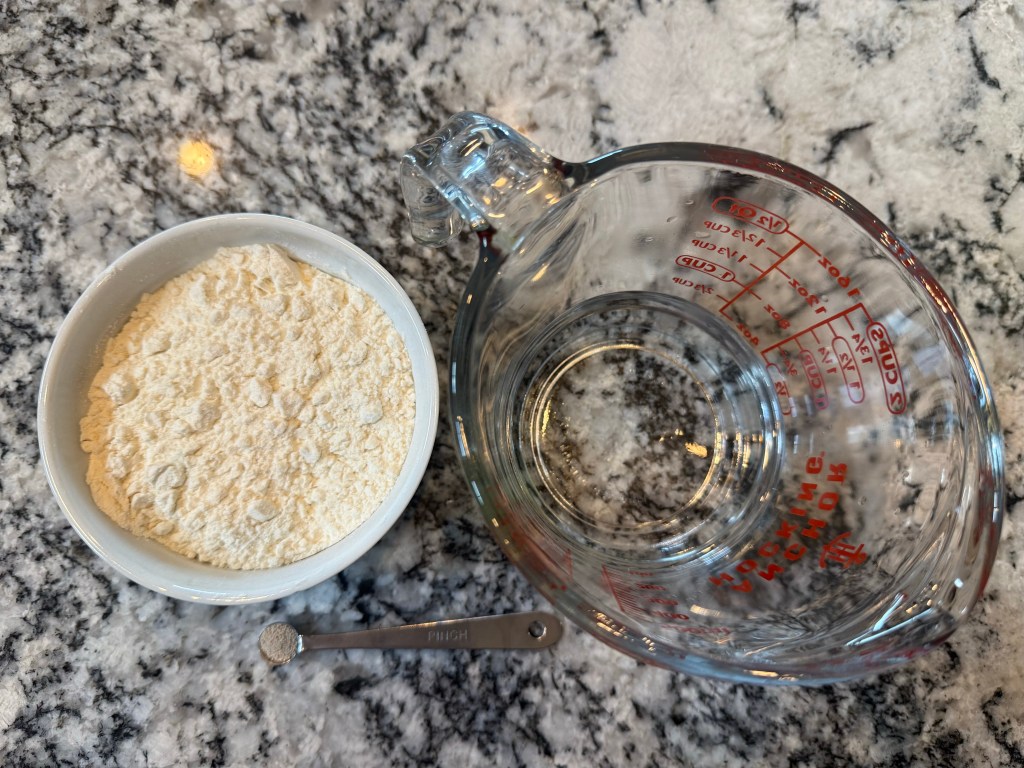

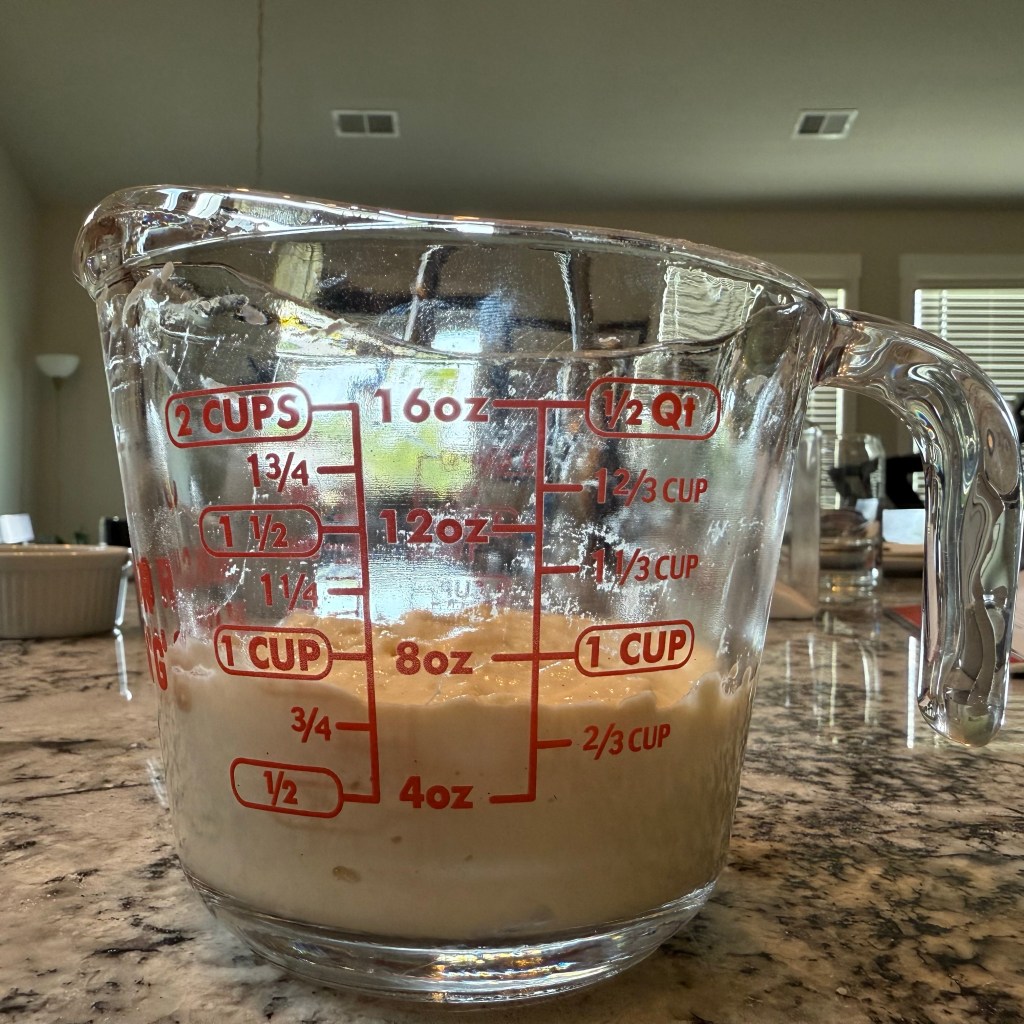

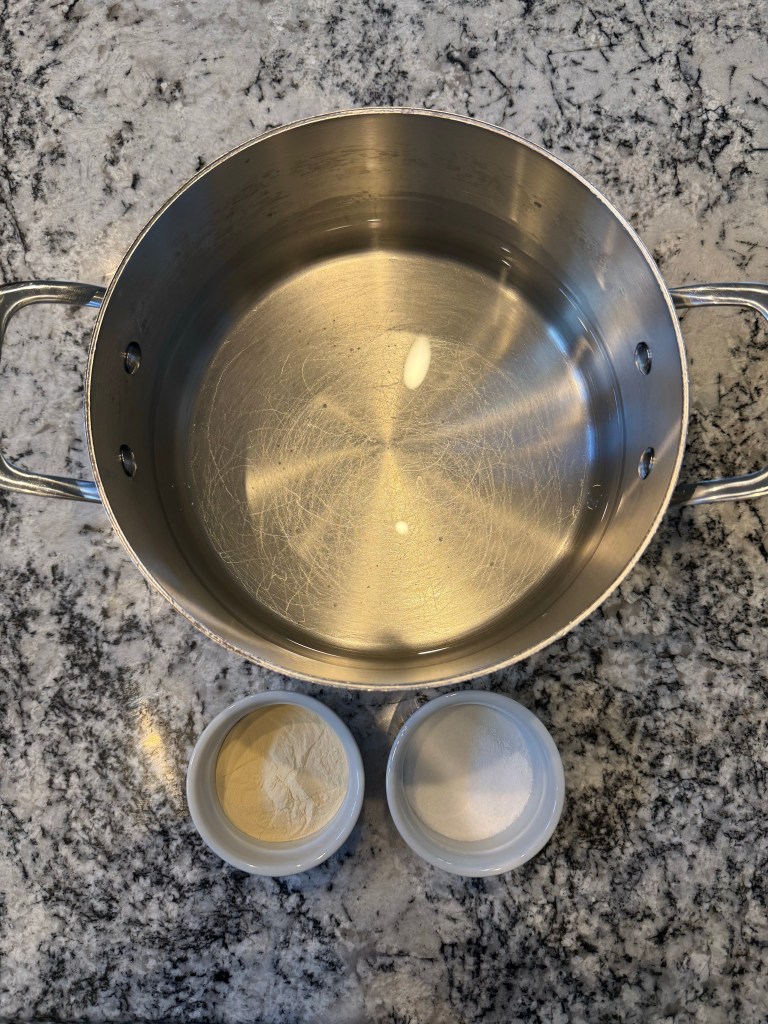

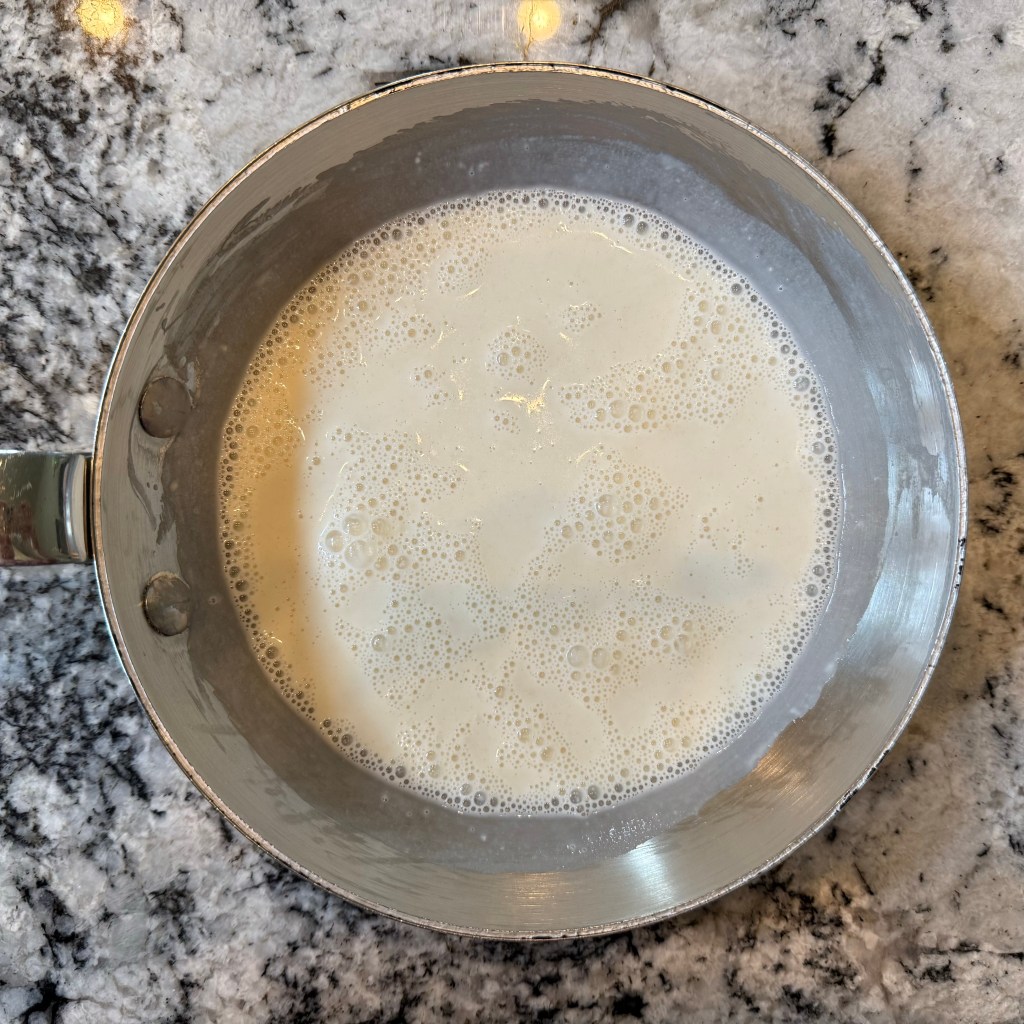

The night before baking I mixed the preferment (a poolish in this case, with equal amounts of flour and water): flour, water, yeast, and time.

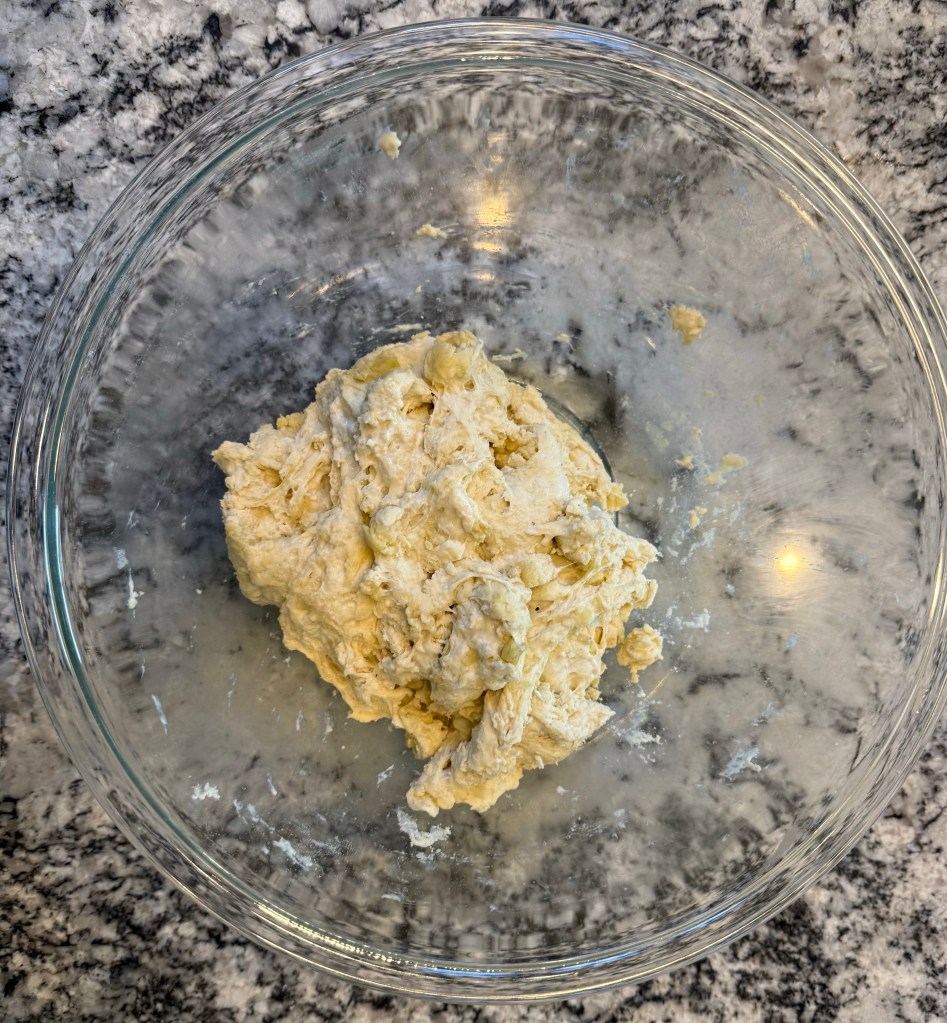

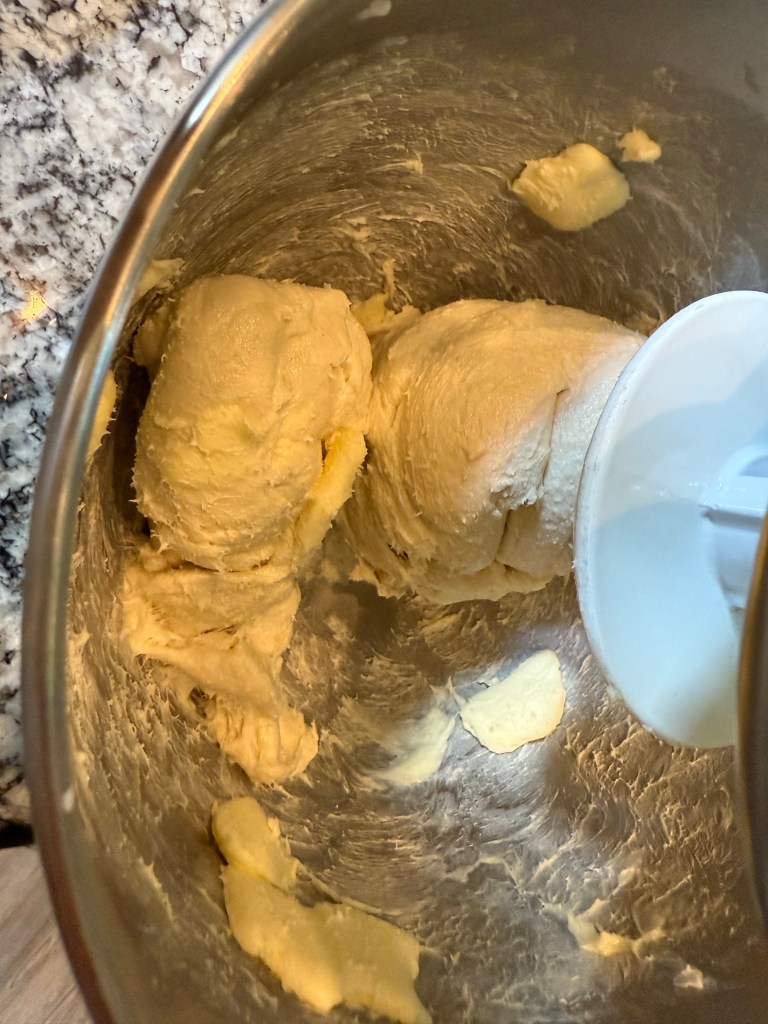

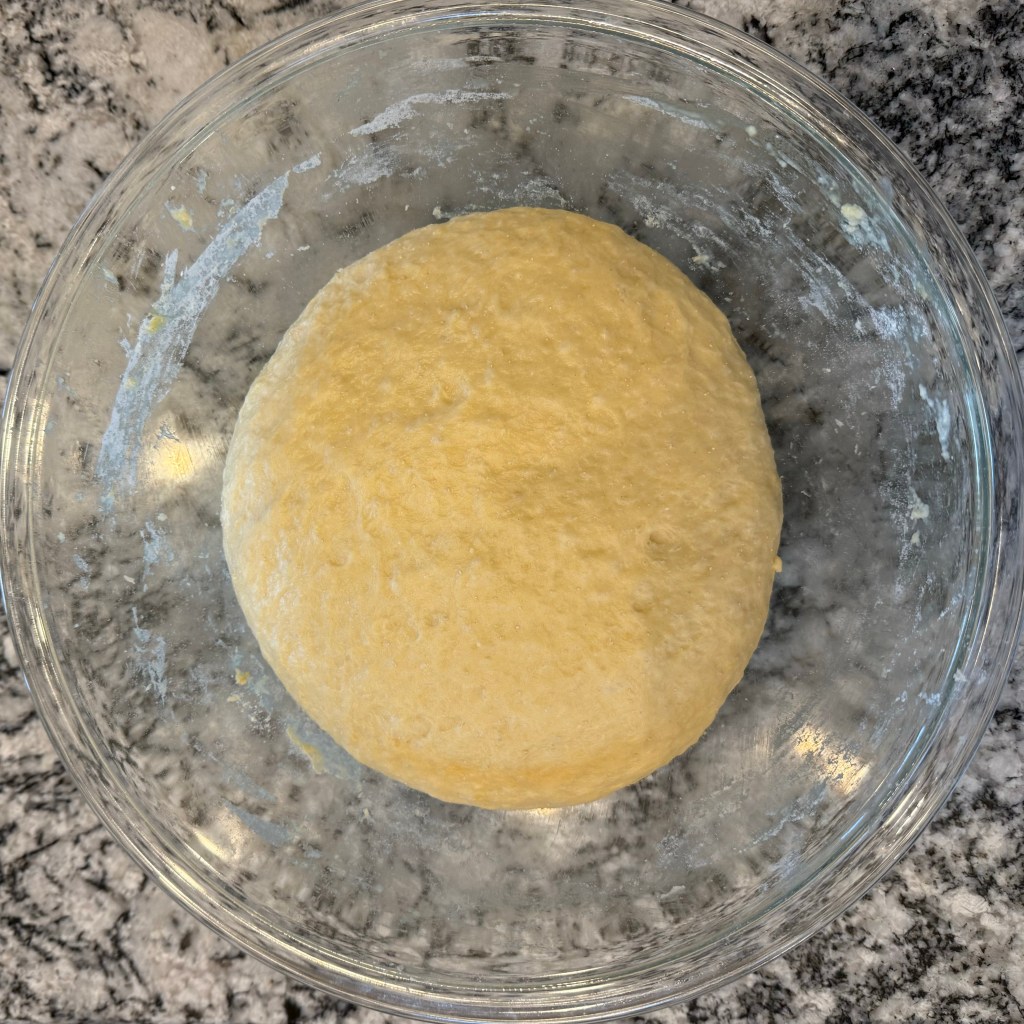

14 hours later I mixed the dough in my KitchenAid mixer. I dislike the feeling of a very sticky dough on my hands, so I prefer to use tools to mitigate the stickiness. After the initial mix I kneaded the dough in the mixer for a few minutes, then covered it and set it aside to rise.

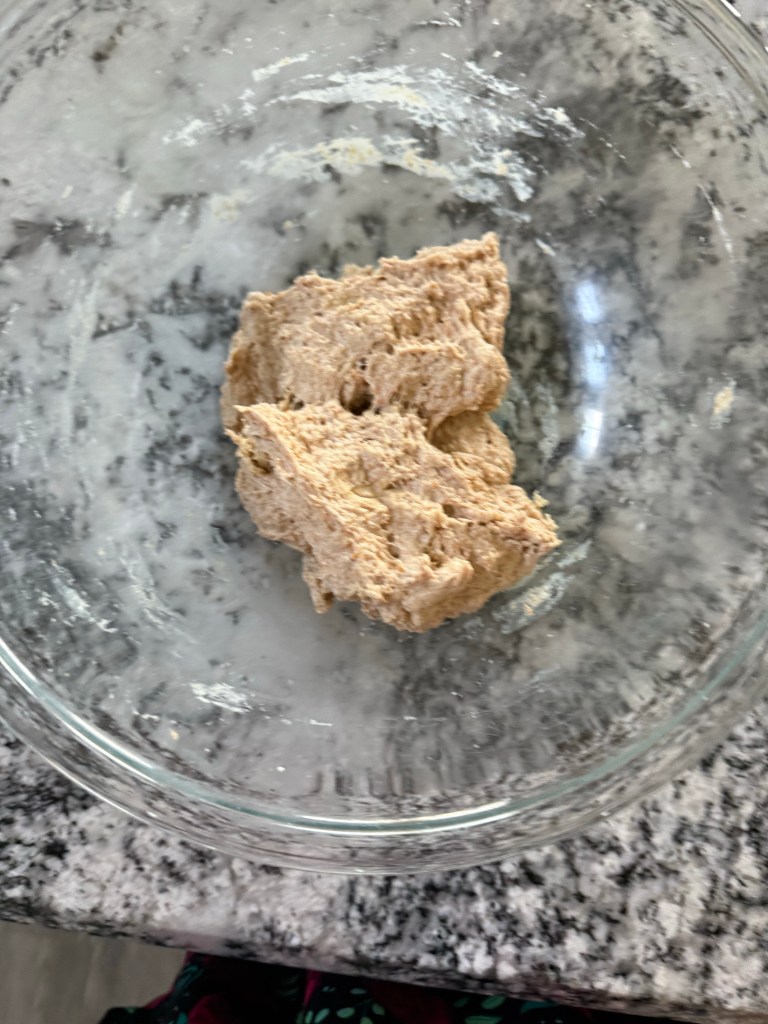

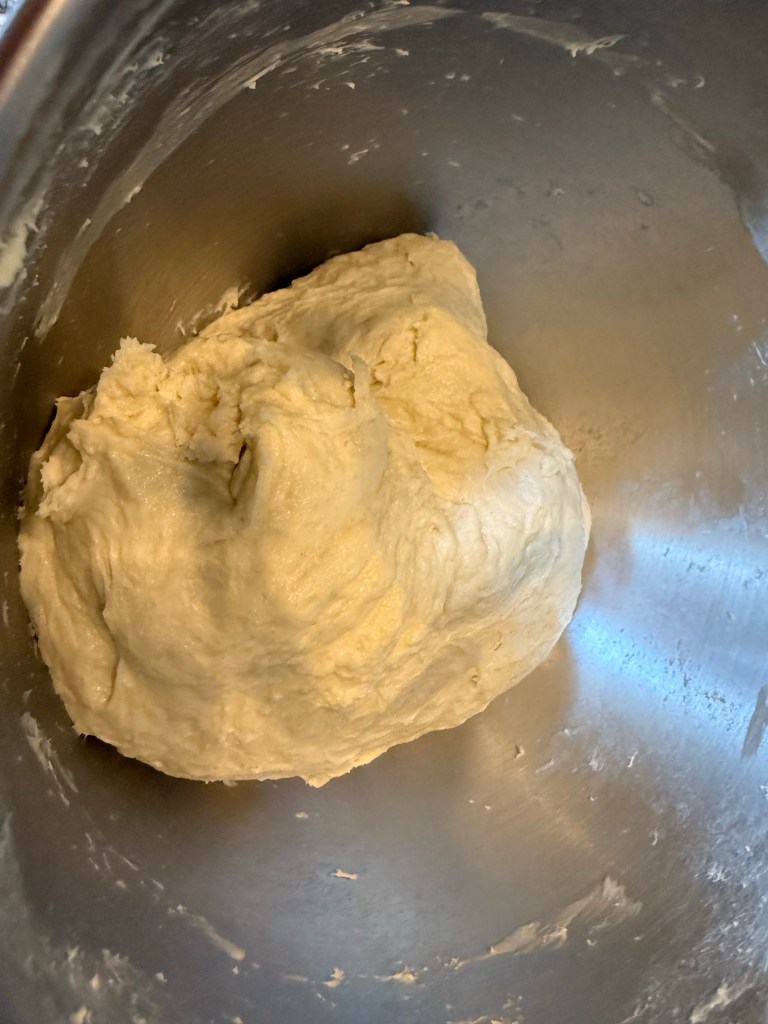

The dough rose for 1 1/2 hours with a fold in the middle to enhance the gluten structure. in the photos below you can see how much the bread rose during this period.

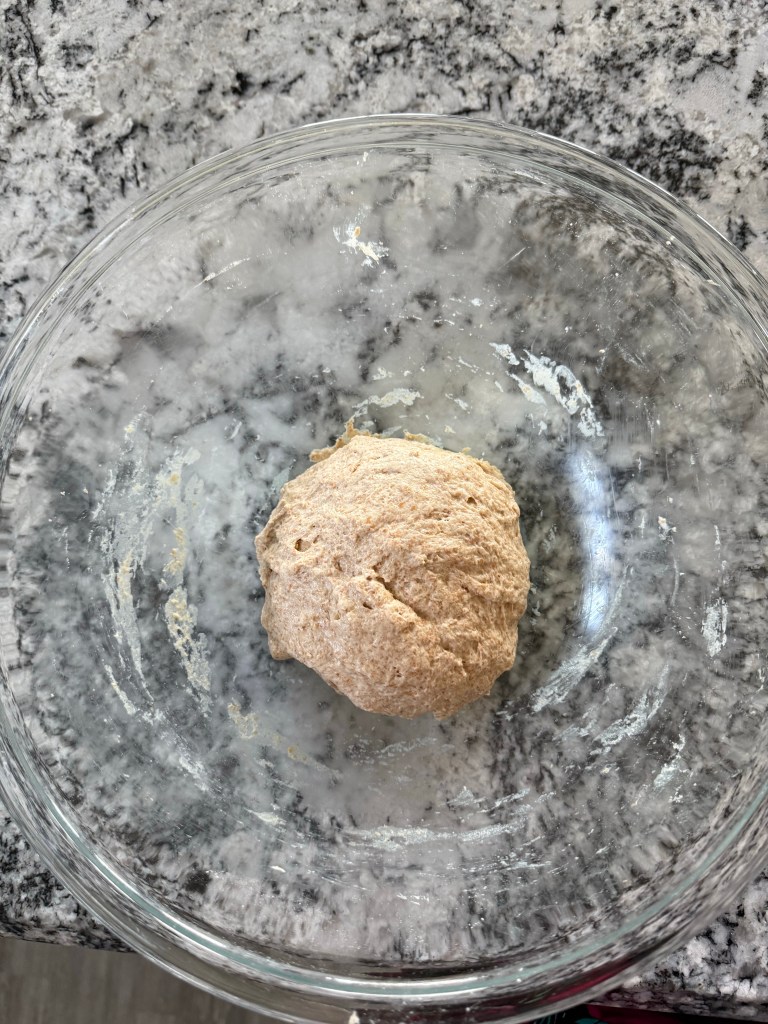

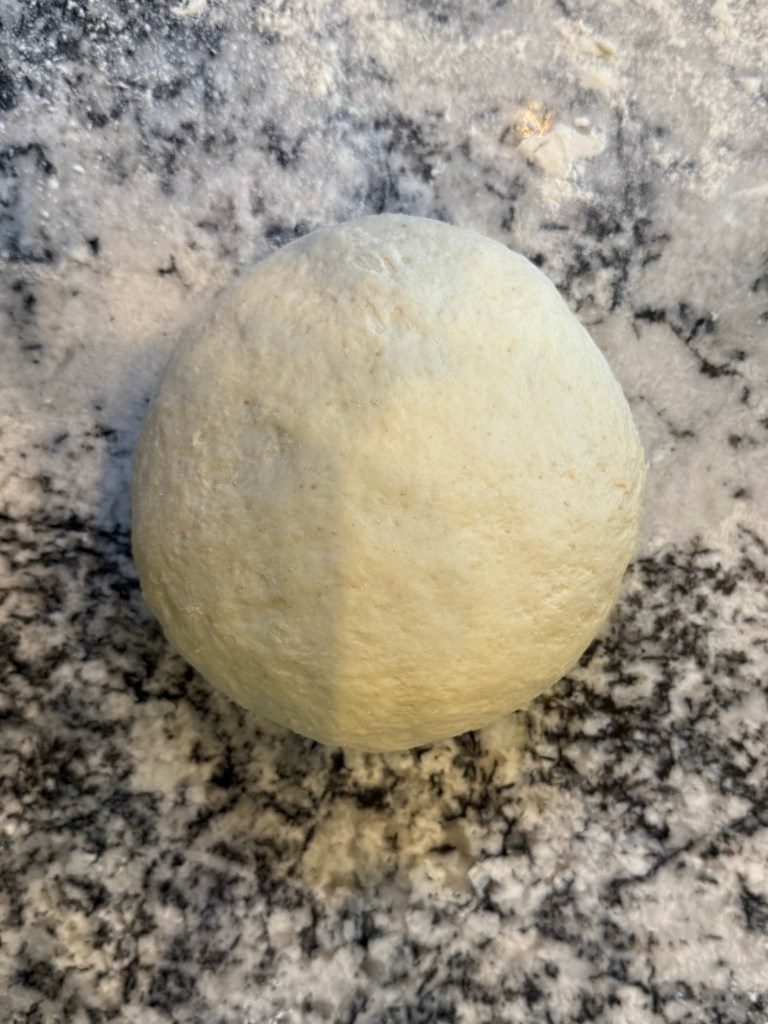

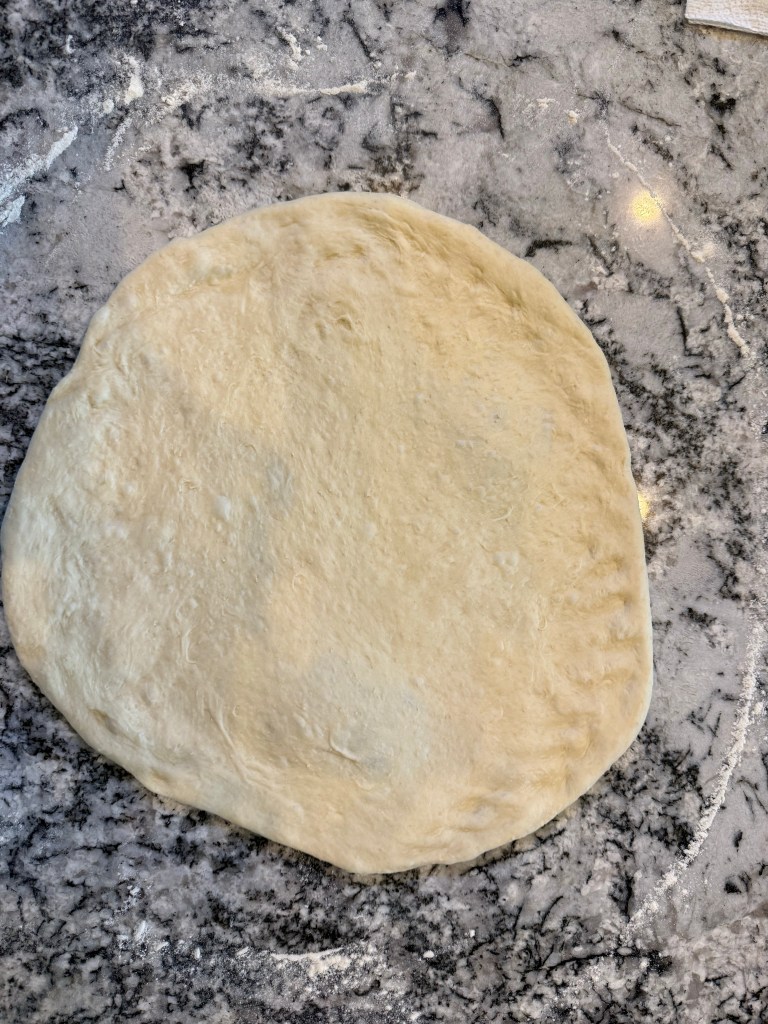

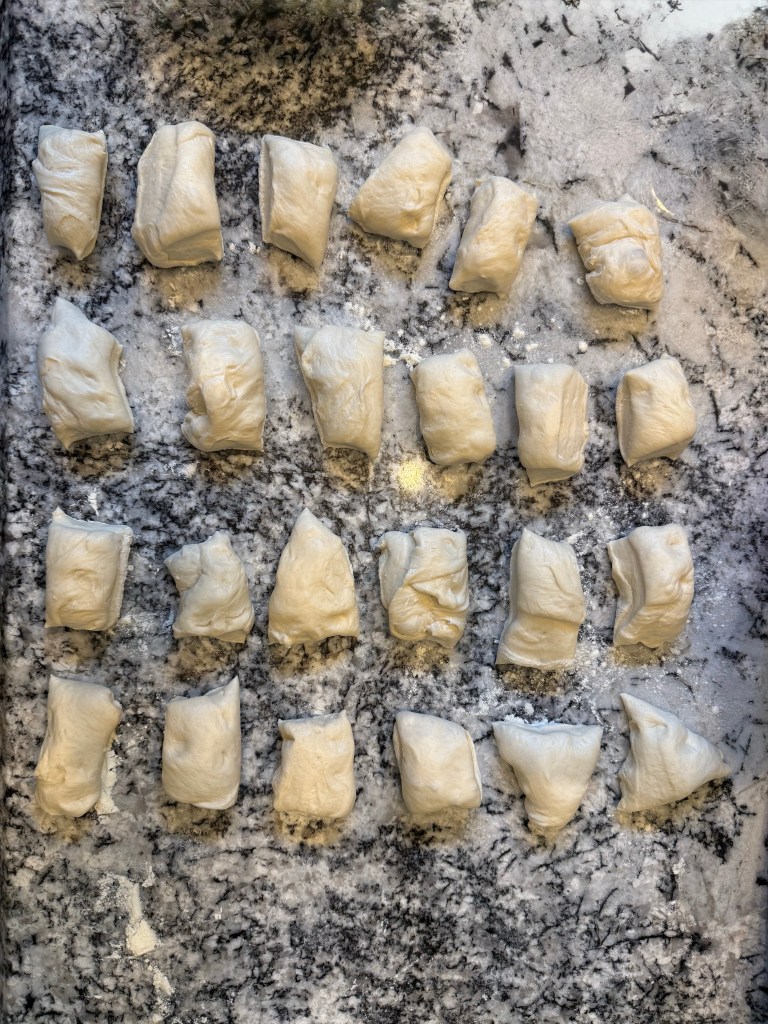

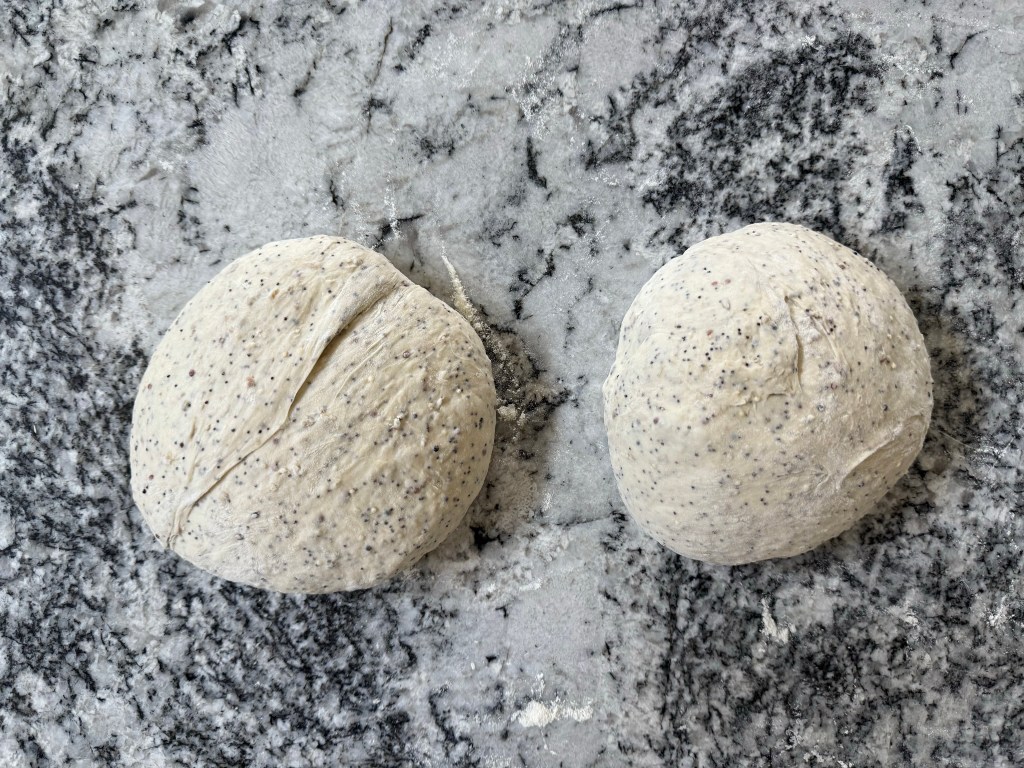

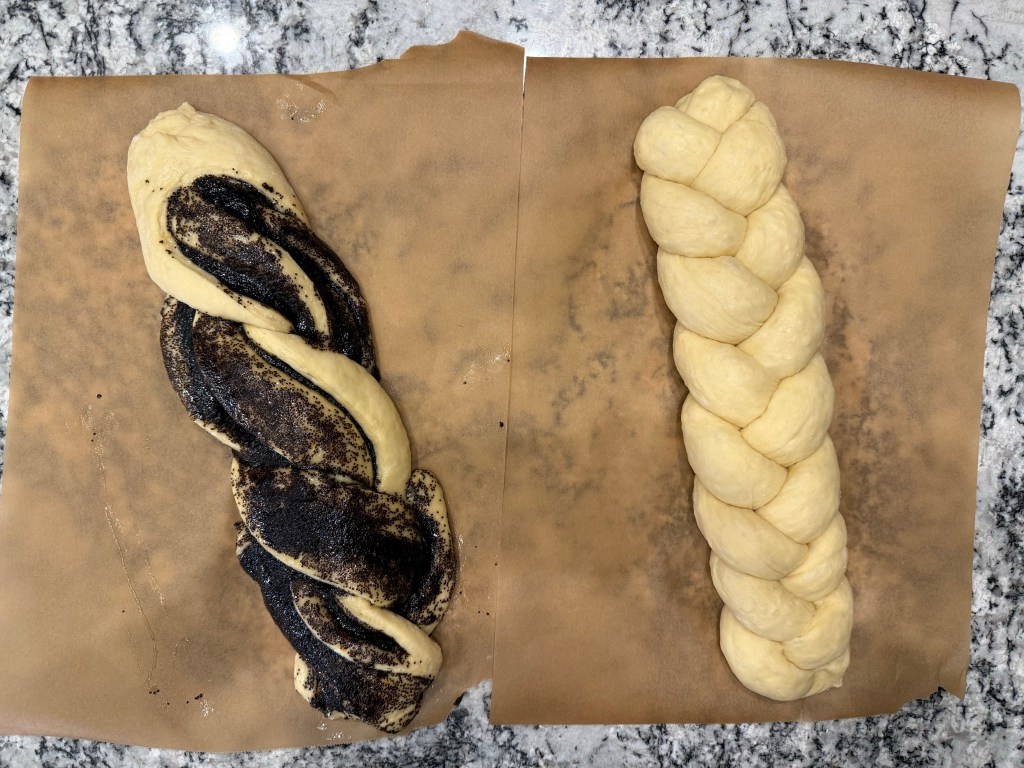

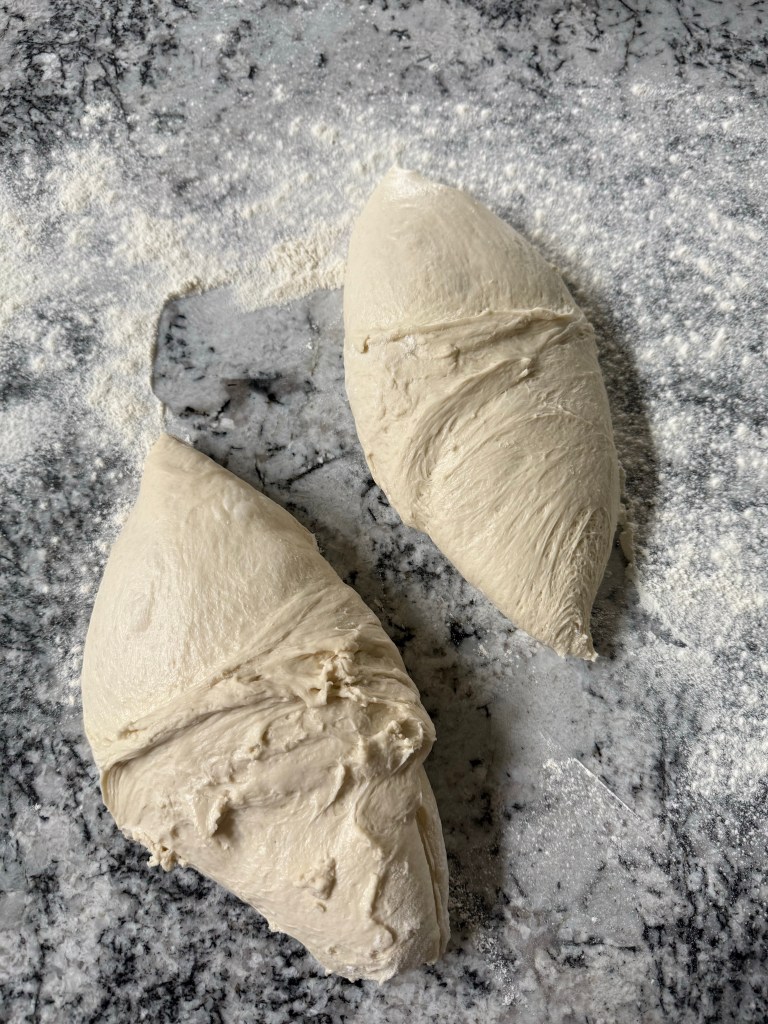

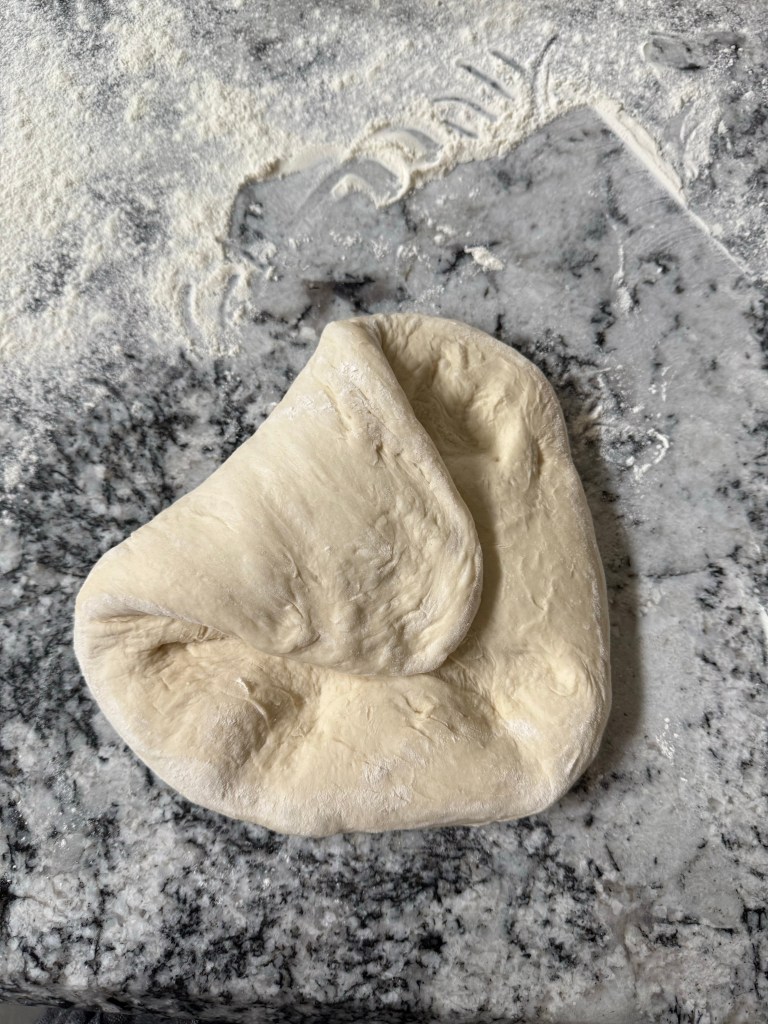

I divided the dough in half by eye, and preshaped each half.

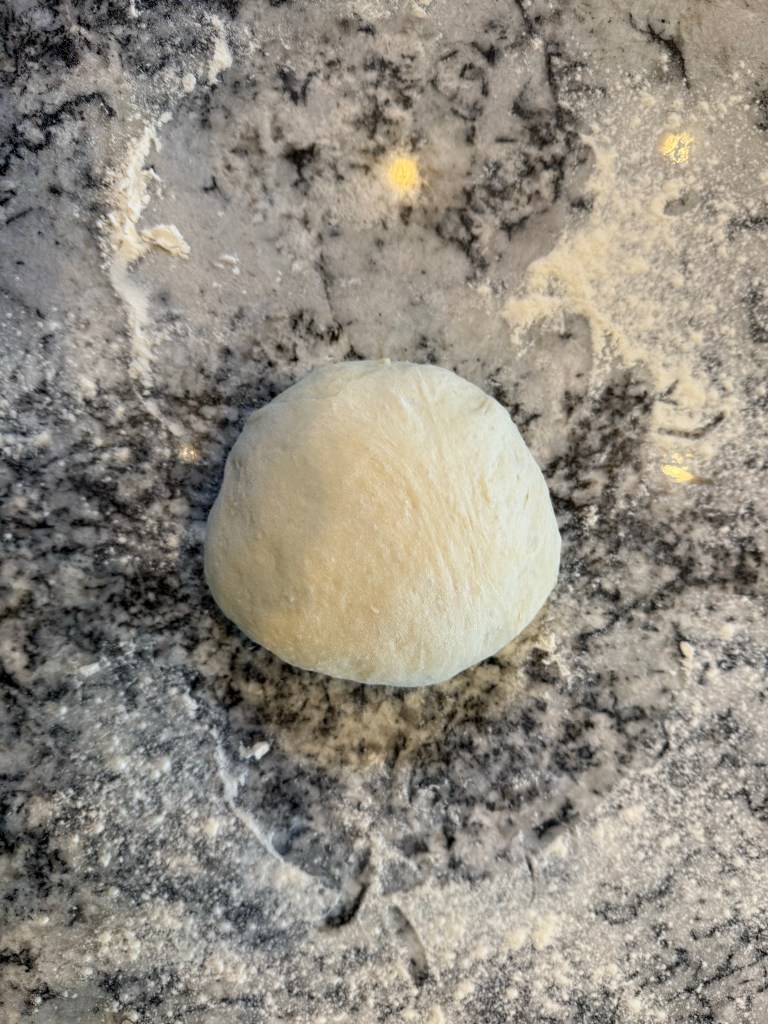

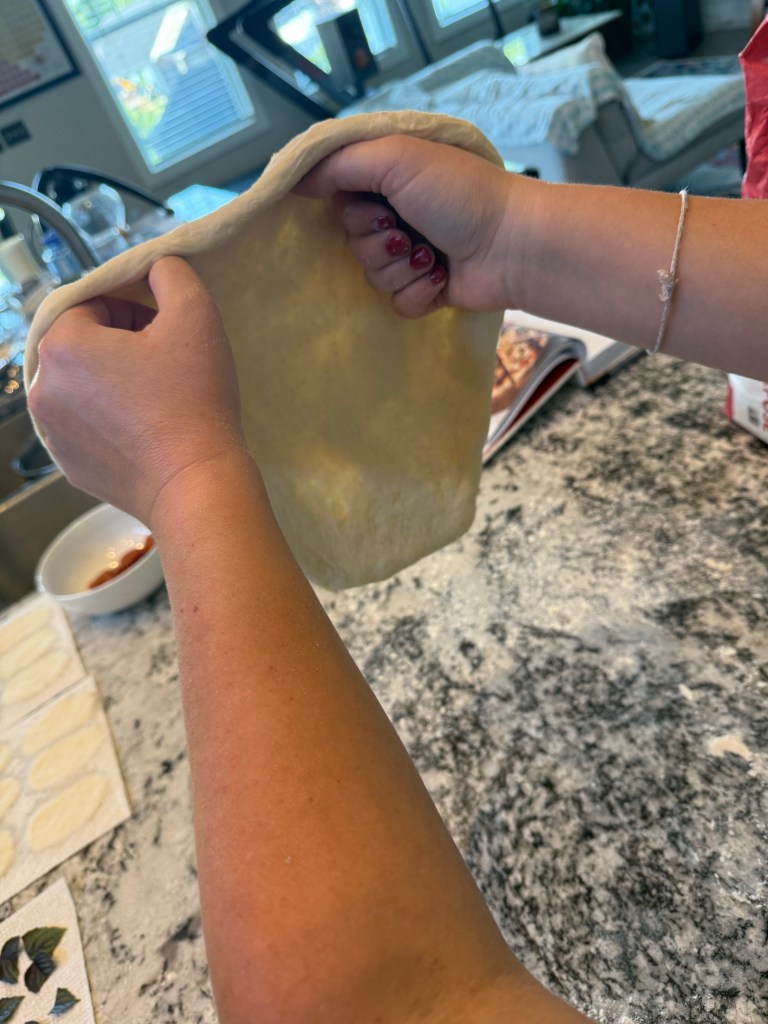

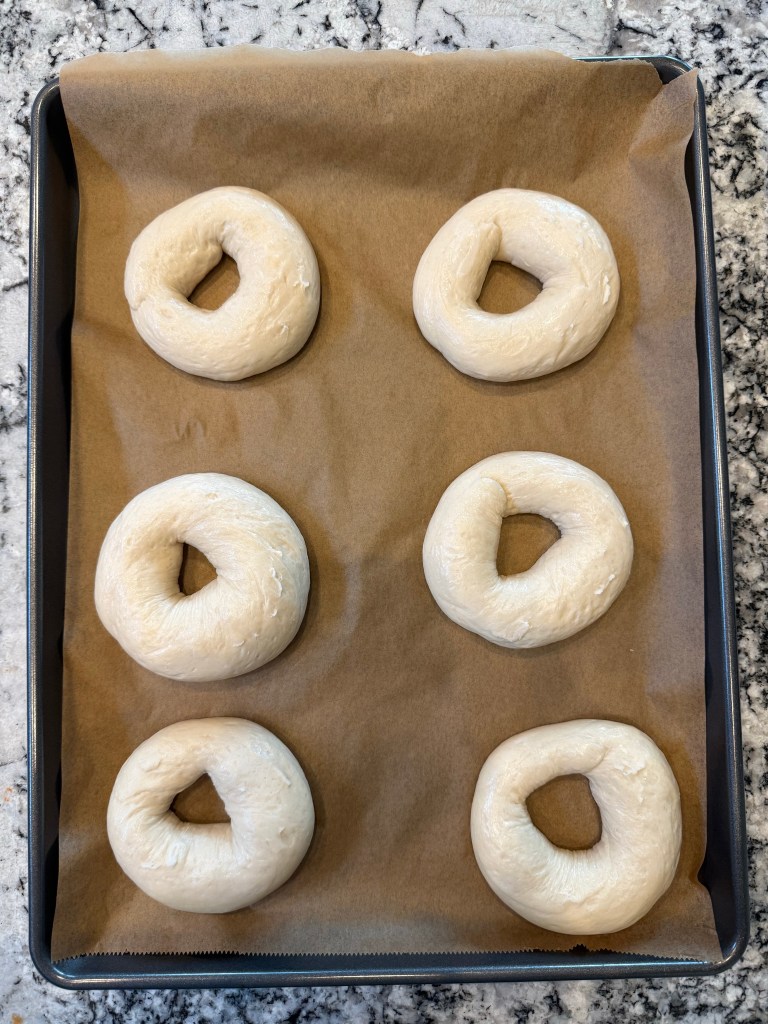

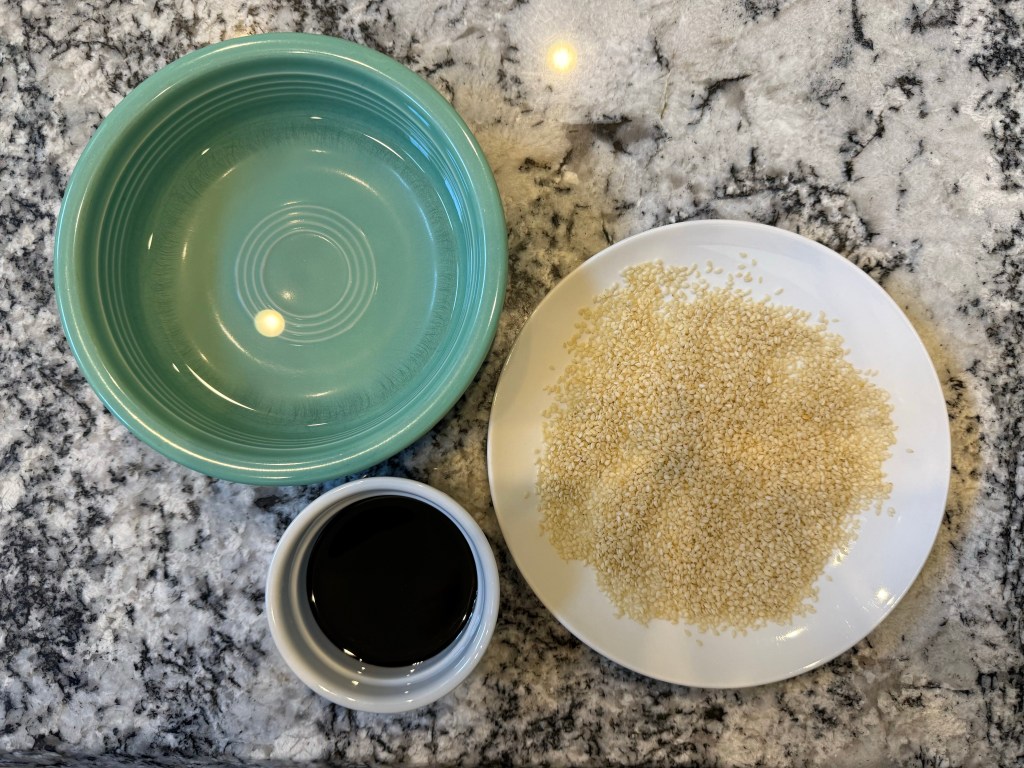

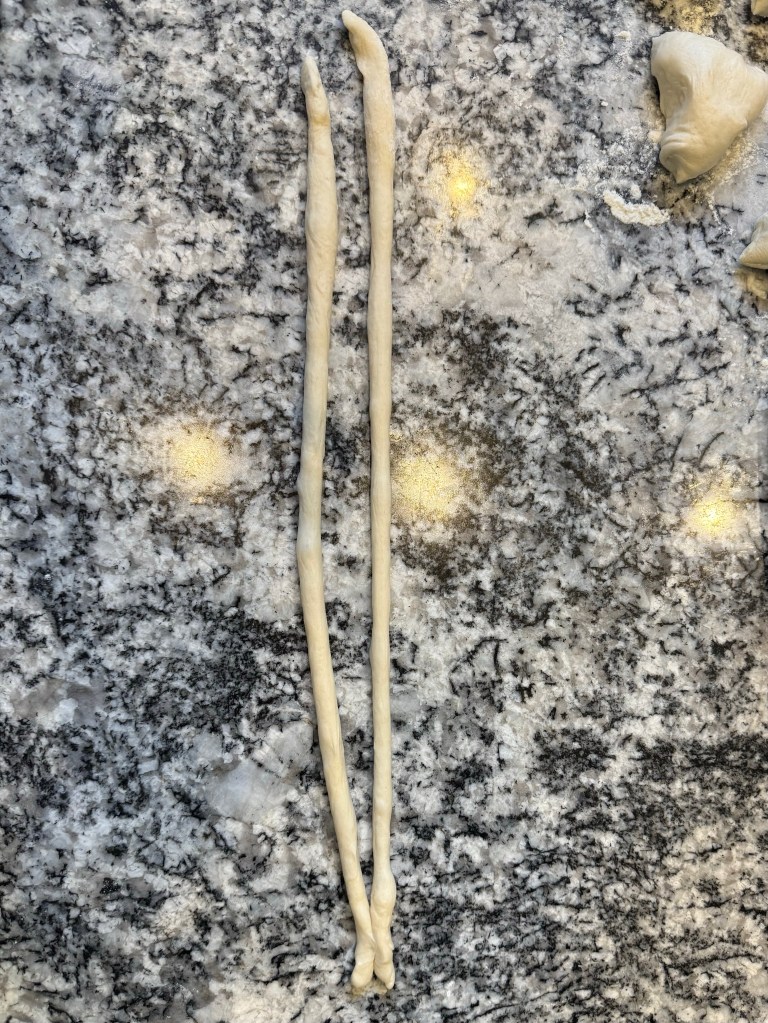

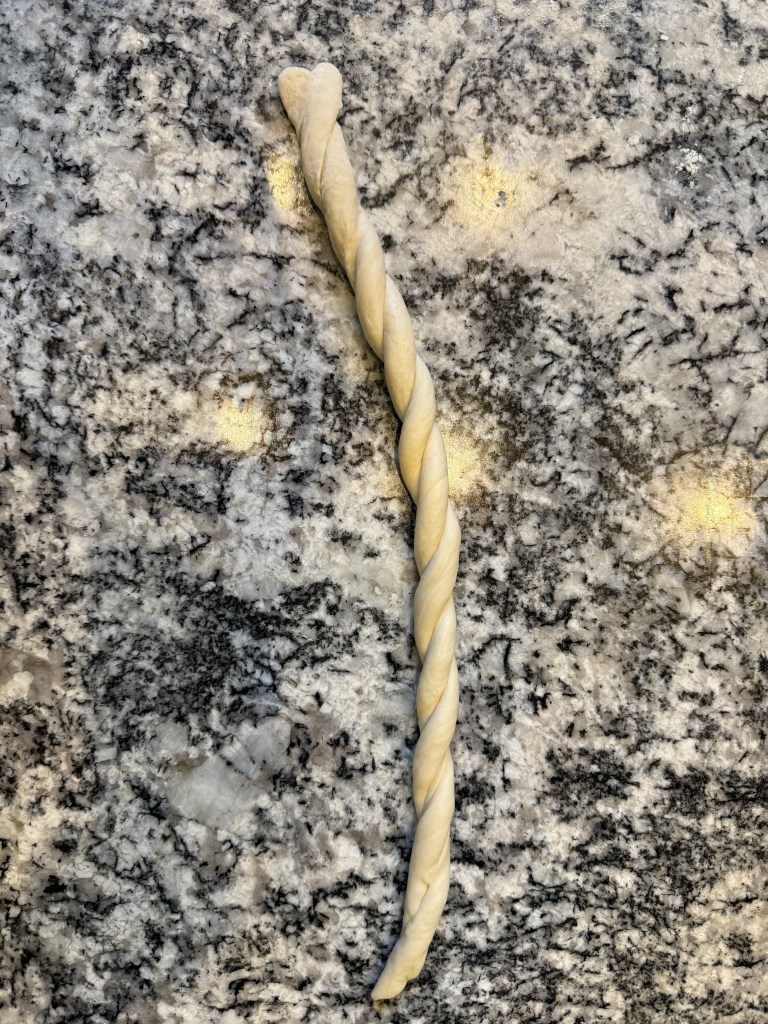

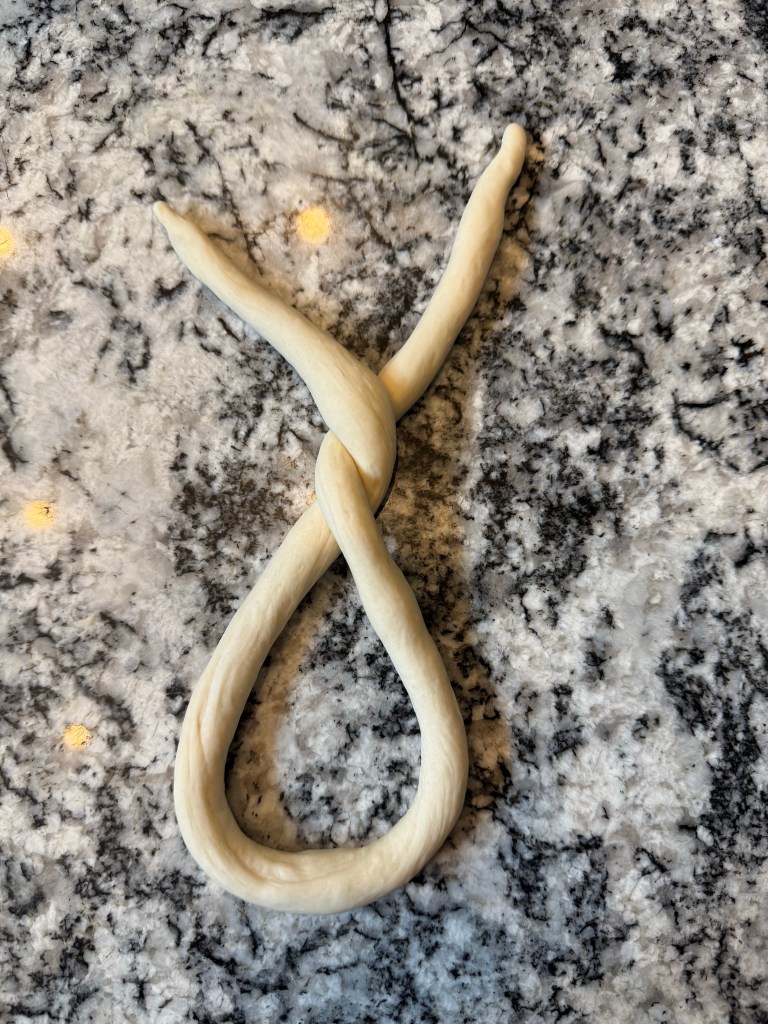

While the preshaped dough rested I floured my bannetons. After 20 minutes I did the final shaping, put the dough in the bannetons (seam-side up), and covered them for the final rise. I also started my oven and my baking vessels preheating.

The bread needed a full hour for its final rise.

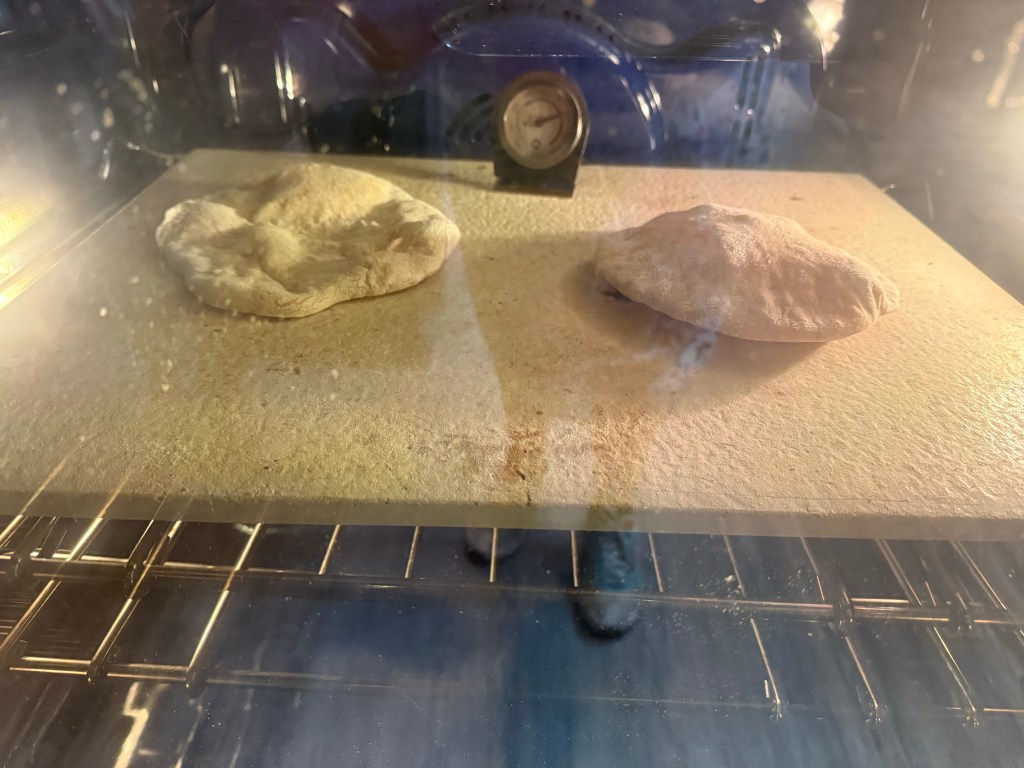

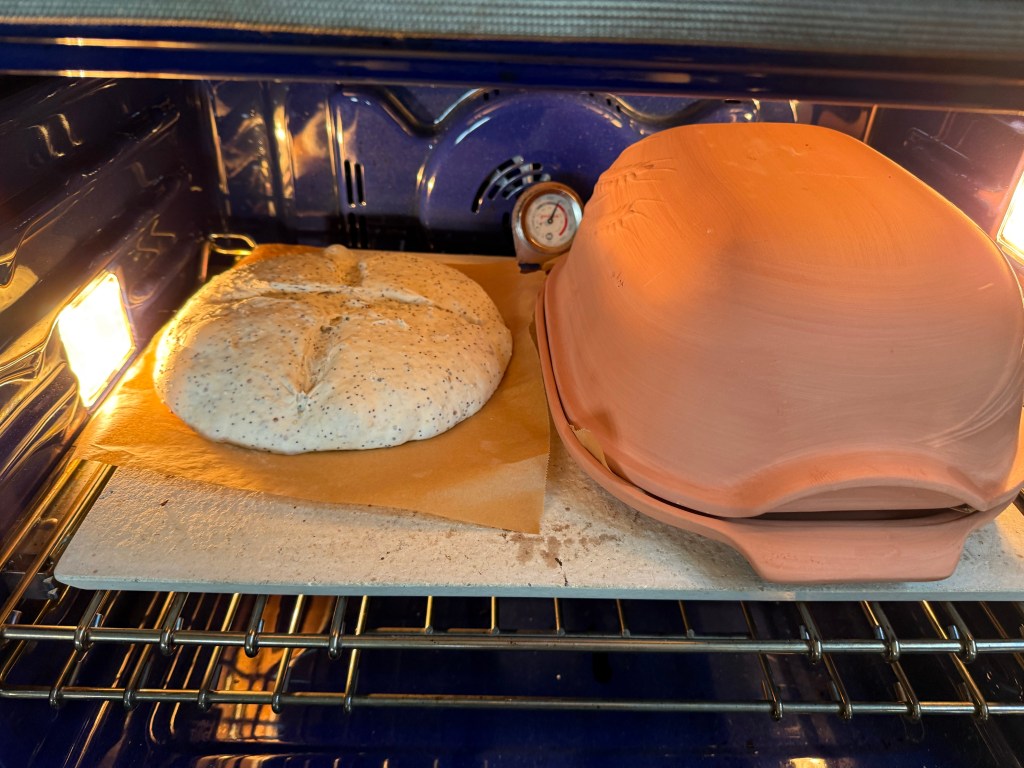

After the final rise was complete I turned the dough out of the bannetons onto parchment paper. I brushed away the excess flour, and scored the dough before putting the dough into my baking vessels and into the oven.

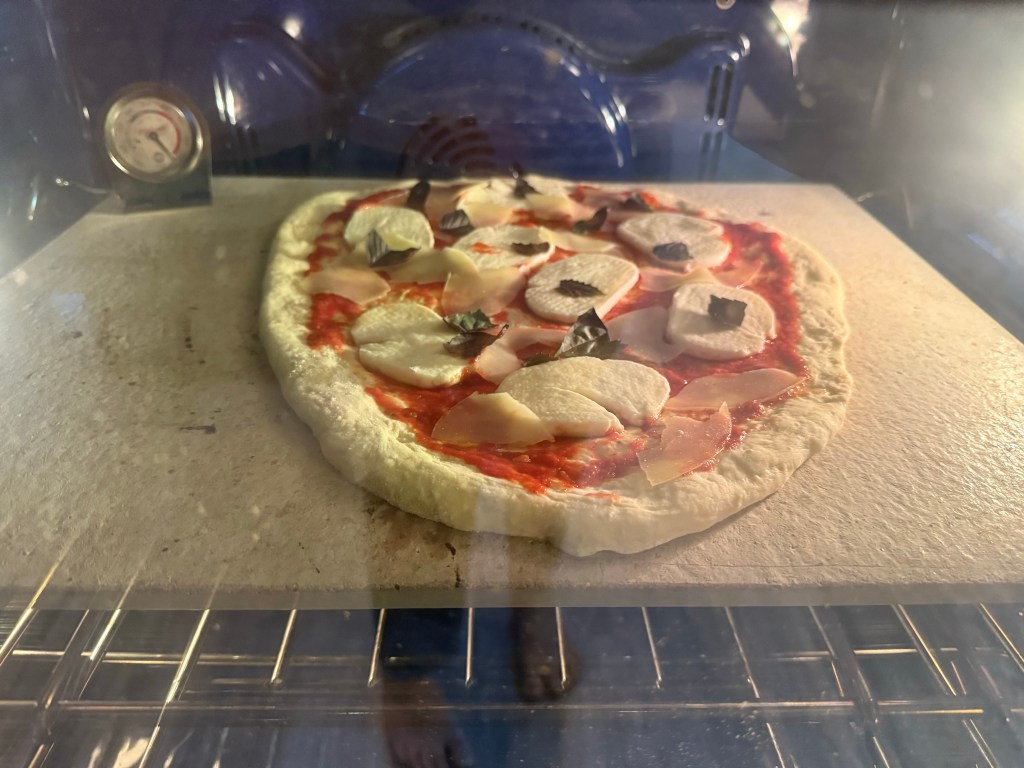

I kept the lids on the baking vessels for 15 minutes to allow the dough to bake with steam. I removed the covers and lowered the oven temperature after 15 minutes.

The bread baked for an additional 30 minutes uncovered (45 minutes total).

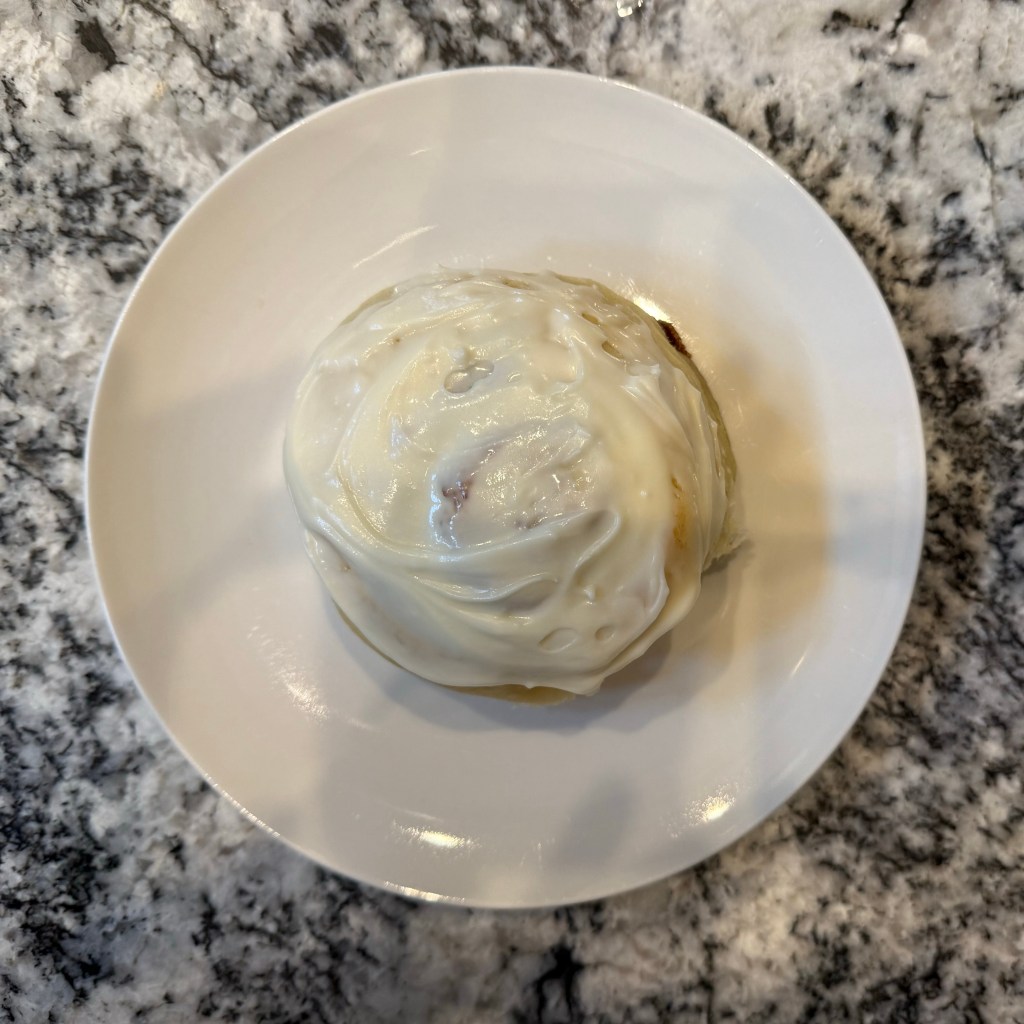

First of all, this bread is pretty. I love how scoring can be decorative as well as functional. Secondly, this bread is delicious. It has a tight crumb with few large holes. It tastes almost like a sandwich bread, except for the thicker, tougher crust. I love a crusty bread. This bread does feel more sophisticated or refined, or maybe less rustic than similar breads made with less yeast and more time.

Until the next time: may your yeast always rise and your flour never run out.